"Living rocks" (Mamallapuram)

TEXT & PHOTOGRAPHS BY BENOY K. BEHL

Mamallapuram, to the south of Chennai on the Tamil Nadu coast, is a marvellous town of temples carved out of rock.

SHORE TEMPLE, 8TH century. It is one of the finest examples of Indian structural stone temples. The Nandis along the outer wall seem to greet and invite one into the sacred space within.

SHORE TEMPLE, 8TH century. It is one of the finest examples of Indian structural stone temples. The Nandis along the outer wall seem to greet and invite one into the sacred space within.

WHILE the early western Chalukyas ruled in present-day Karnataka, by the end of the 6th century A.D., the Pallava rulers from present-day Andhra Pradesh extended their control southwards over much of Tamil Nadu. They created the first large empire of South India. It is from the time of the rule of the Pallava king Mahendra, from A.D. 600 to A.D. 630, that numerous inscriptions have been found and Pallava history is documented.

DESCENT OF THE Ganga, 7th century. This vast rock in the ancient port town has been transformed into a world teeming with beings: human, animal and divine. This is one of the most marvellous creations in the whole of Indian art.

DESCENT OF THE Ganga, 7th century. This vast rock in the ancient port town has been transformed into a world teeming with beings: human, animal and divine. This is one of the most marvellous creations in the whole of Indian art.

On the Tamil Nadu coast, is a marvellous town of temples carved out of rock. Mamallapuram, or Mahabalipuram, was one of the greatest sea ports of ancient times. In those times this bustling town would have had a cosmopolitan culture. In its markets, people from South-East Asia would have rubbed shoulders with Romans. Coins found here testify to extensive trade with Rome and other places from at least the 1st century. Colonies of Romans are also known to have been present in this part of Tamil Nadu at that time.

This port town was called Mamalai, or “great hill”. Mahendra’s successor, Narasimhavarman, known as Mamalla (or the “Great Warrior”), expanded the facilities of the port. He changed its name to Mamallapuram, or “city of Mamalla”. Ships sailed constantly from here to Sri Lanka and South-East Asia.

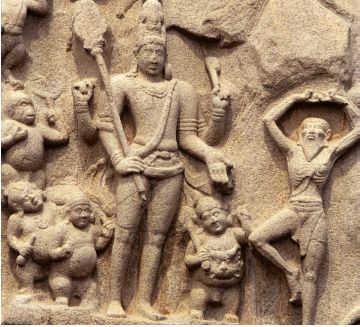

SIVA WITH HIS many "ganas" around him. They represent those persons who have spent a lifetime devoted to him and have been granted the boon of remaining perpetually close to him. An ascetic is seen doing penance.

SIVA WITH HIS many "ganas" around him. They represent those persons who have spent a lifetime devoted to him and have been granted the boon of remaining perpetually close to him. An ascetic is seen doing penance.

Here, over perhaps a hundred years, from about A.D. 630 to A.D. 728, marvellous monuments were cut out of outcrops of hard grey granite. Cliff faces were transformed into a teeming world of animals and people. Boulders were carved into fine temples. Rocks were chiselled into the shapes of animals. The magnificent temples of Mamallapuram reflect the fully developed styles of South Indian temples. Obviously, such temples must have been made for a long time before this period. The earlier ones must have been made out of ephemeral materials and have not survived.

Facing the ancient port and not very far from it is one of the marvels of the sculptural art of India. The face of a vast granite rock, almost 100 feet (30.5 metres) by 50 feet (15.25 m), has been transformed into a world of divine and earthly beings. This giant relief is believed to be of the early or middle 7th century.

DIVINE FIGURES AND "kinnaras" populate the upper parts of the tableau. "Kinnaras", or composite creatures, part human and part bird, are perennial images in Indian art, from earliest times. These embody the Indic vision of the oneness of the whole of creation.

DIVINE FIGURES AND "kinnaras" populate the upper parts of the tableau. "Kinnaras", or composite creatures, part human and part bird, are perennial images in Indian art, from earliest times. These embody the Indic vision of the oneness of the whole of creation.

The tableau presents the auspicious moment of the descent of the river Ganga to bestow her blessings and her treasure of fertility on the world. Some scholars have also interpreted this scene to be a depiction of the penance of Arjuna, the hero of the epic Mahabharata. A deep cleft in the rock has been artfully used to represent the great river as she descends. In fact, a storage tank was made above it. On ceremonial occasions, water must have been let out to rush down the cleft, giving a sense of reality to the sacred scene.

The teeming world of a forest has been created around the river. About a hundred figures of animals, men, women and divine beings all turn in reverence towards the life-giving river. These are all made approximately life-sized and naturalistic and with great sensitivity. Bhagiratha, the sage, is seen performing penance and imploring Siva to bear the force of the fall of the river from heaven.

DIVINE NAGAS AND Naginis swim up the river as the Ganga descends from the heavens. These beings, which are part human and part serpent, are among the oldest images of Indic art. They represent fertility as well as the protective forces of nature.

DIVINE NAGAS AND Naginis swim up the river as the Ganga descends from the heavens. These beings, which are part human and part serpent, are among the oldest images of Indic art. They represent fertility as well as the protective forces of nature.

Next to him stands Siva, whose gesture indicates that he is granting a boon to the ascetic. Nagas and Naginis, divine serpents who live in the waters, are shown swimming up the river. Below Siva we see a shrine of Vishnu, with an elderly sage and his disciples before it. Beside the river, other ascetics perform puja and penance.

On the opposite bank is a charming depiction of a cat performing penance. He has deluded some mice into believing that he is an ascetic. This could be a story from the Mahabharata in which a sad fate overtakes the trusting mice. It could also be a witty comment being made by the artists on hypocrisy in contemporary practices.

DESCENT OF THE Ganga, another detail. Even as these figures fly through the skies, their expressions inform one about another reality, one that is deep within and not in the activity of the outside world.

DESCENT OF THE Ganga, another detail. Even as these figures fly through the skies, their expressions inform one about another reality, one that is deep within and not in the activity of the outside world.

The many beings that populate the world created around the river are made with a great sense of liveliness. In these beings there is a sense of freedom and the joy of creation expressed by the artists.

In Indic vision, there is no marked division between the divine and the earthly. All that there is, is sacred. There is a grace that underlies all that there is. Our response to that grace when we see it is considered to be a moment when we get a glimpse of the Truth. Bringing this realisation to us is the purpose of Indian art. All forms and all deities are a means towards the realisation of the inherent unity of the whole of creation.

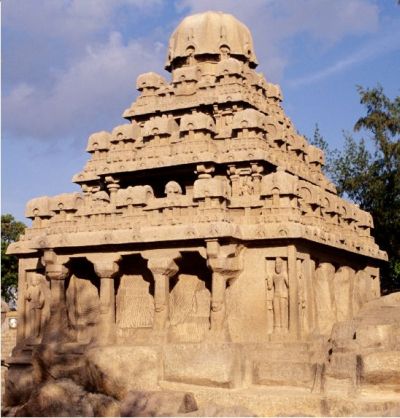

BHIMA RATHA, MID- to late 7th century. The barrel-shaped roof has been one of the designs in Indian temples from early times. It is often seen in the case of apsidal temple structures.

BHIMA RATHA, MID- to late 7th century. The barrel-shaped roof has been one of the designs in Indian temples from early times. It is often seen in the case of apsidal temple structures.

The world as seen by the early Indic artist has a sense of sublime continuity in all living things, whether animal, vegetable or divine. It is like a fabric with a continuous texture or a great tapestry of interconnected things. If one were to cut or break one part of this tapestry, one would damage the whole. That is the spirit that animates all Indic faiths. Here the hard stone face of the granite cliff is cajoled into elaborating this very profound and contemplative approach to the universe.

The realism and lifelike softness of the elephants in one of the reliefs are remarkable. The details of the baby elephants show the artists’ deep concern for all beings. Another detail, of a deer scratching its nose, shows the artists’ great sensitivity and keen observation of the natural world. Close by is another relief depicting the same subject. However, it is unfinished.

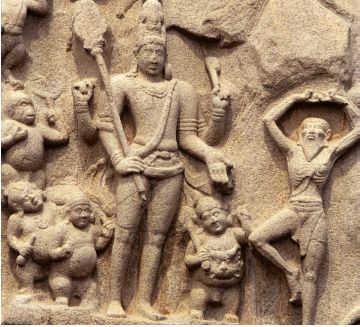

DHARMARAJA RATHA, MID- to late 7th century. This is another unfinished temple of the group of five "rathas". It is a replica of the most popular form of the South Indian temple structure. The superstructure has three storeys, which diminish in size as they ascend.

DHARMARAJA RATHA, MID- to late 7th century. This is another unfinished temple of the group of five "rathas". It is a replica of the most popular form of the South Indian temple structure. The superstructure has three storeys, which diminish in size as they ascend.

A little to the left of the great “Descent of the Ganga”, a Krishna Govardhan scene is carved out of a boulder. Krishna holds up the Govardhan mountain to protect a village from the fury of a storm. It is a charming scene. With peace restored and the storm forgotten, a cowherd plays the flute and another milks a cow. This is one of the finest depictions in Indian art of rustic life. In Pallava times, when this relief was made, there was no mandapa in front of it. Therefore, it would have been possible to see clearly the whole mountain above Krishna as he lifted it. In later times, with the coming of more formalised norms, a mandapa was made in front of the scene to accord due status to the deity. The effectiveness of the theme was then largely lost.

The soft rendering and slender forms of the Pallava idiom can again be seen in the Varaha mandapa of around the middle of the 7th century. Here the development of Pallava iconography and architectural styles can also be seen. The seated lions made on the bases of pillars are characteristic.

VARAHA CAVE, MID-7TH century. To fight the evil of ignorance, Vishnu is envisaged as descending upon the earth in the powerful Varaha "avatara", that is, in the form of a boar. Varaha is believed to have saved the Earth goddess, Bhu Devi, from drowning. This myth represents the great power within us that can save us from the ocean of ignorance.

VARAHA CAVE, MID-7TH century. To fight the evil of ignorance, Vishnu is envisaged as descending upon the earth in the powerful Varaha "avatara", that is, in the form of a boar. Varaha is believed to have saved the Earth goddess, Bhu Devi, from drowning. This myth represents the great power within us that can save us from the ocean of ignorance.

There are four major sculptural panels in the cave. Vishnu is shown in the Varaha avatara saving the Earth goddess, Bhu Devi, from being submerged in the ocean. All Indian myths operate at many levels, and saving Bhu Devi also signifies the saving of mankind from the ocean of ignorance. Vishnu is also presented in the form of Trivikrama, the conqueror of the three worlds. The rear wall of the cave has Gajalakshmi on it. Lakshmi, who represents prosperity, is shown here being lustrated by elephants. Also on the rear wall is a relief of Durga, who represents victory over ignorance.

In Pallava art, the figures are slender and delicately made. The scale is naturalistic. A depth is given to the relief by figures that turn inwards and others that are seen from the back. Such arrangements of figures were also seen in the paintings of Ajanta of the 5th century and in the art of the Krishna Valley in Andhra Pradesh.

One of the most magnificent depictions in Mamallapuram is that of Mahishasuramardini made in a 7th-century cave. It is entirely different from earlier representations of this subject. Durga battles the demon buffalo, or Mahisha, who represents the evil of ignorance. It is a most animated scene, and unlike before, the scale is naturalistic. Here, the demon has a human body and the head of a buffalo. The natural poses of the figures, advancing from one side and pulling back upon the other, enhance the drama and realism of the subject. The self-assured ganas of Durga’s army of Righteousness are unforgettable.

KRISHNA MANDAPA, 7TH century. This is an endearing image of a cow being milked while she lovingly licks her calf. Such depictions bring the village scene made in this cave to life.

KRISHNA MANDAPA, 7TH century. This is an endearing image of a cow being milked while she lovingly licks her calf. Such depictions bring the village scene made in this cave to life.

The Adivaraha cave is notable for having portraits of King Narasimhavarman with his queens. There is also a representation of his son with his wives. After the period of the Kushanas, who hailed from southern China and had portraits of themselves made in royal shrines in the 1st century, these are the earliest surviving portraits of Indian kings.

In early India, the purpose of art was always to take one’s thoughts away from the passing reality of the world to that which was eternal. Therefore, art did not traditionally depict ephemeral personalities. From here onwards, a shift takes place and the emphasis begins to come upon the personality of monarchs.

There are nine monolithic free-standing temples cut out of boulders. Five of them are in one group. These are the earliest such edifices in India to be carved out of rock, both on the outside and the inside. They are called rathas, or temple chariots. This is a misnomer as they are meant to be temples. They are a marvellous record in stone of the many forms of temple architecture in South India at that time.

ELDERLY MAN AND child, Krishna Mandapa. Amid all the grandeur of divine themes, the pulsating details of life are not forgotten by the artist. This delightful detail appears on one side of a Krishna Govardhan scene.

ELDERLY MAN AND child, Krishna Mandapa. Amid all the grandeur of divine themes, the pulsating details of life are not forgotten by the artist. This delightful detail appears on one side of a Krishna Govardhan scene.

The monoliths are named after the five Pandava brothers of the Mahabharata and their common wife Draupadi. They form a coherent group and were probably made in the middle of the 7th century. The smallest temple is called the Draupadi Ratha. It has a curved roof, which is believed to be modelled after the thatched roofs of that period. The shrine is dedicated to Durga. The lion on which she rides is outside the temple.

Arjuna’s ratha is on the same platform as the Draupadi Ratha. This is an early example of a developed Dravida, or South Indian, style temple. The two-tiered pyramidical roof is capped by a domelike element called a stuti. In South India, the term shikhara refers to this crowning element, whereas in North India shikhara means the whole temple tower. The half figures on the upper levels convey the impression that they are partly hidden because of the viewer’s perspective from below. Bhima’s ratha is a rare record of a barrel-vaulted type of temple. The long shape is appropriate for the large depiction of the Anantasayana Vishnu, which remains unfinished inside.

ADIVARAHA CAVE. AFTER the 1st century A.D., the period of the Kushana rulers, it is the Pallava period that brings us the first portraits of rulers in India. King Narasimhavarman is depicted here.

ADIVARAHA CAVE. AFTER the 1st century A.D., the period of the Kushana rulers, it is the Pallava period that brings us the first portraits of rulers in India. King Narasimhavarman is depicted here.

The unfinished Dharmaraja Ratha is the largest of the group. Inscriptions with the name of Narasimhavarman I suggest that the temple was begun in his time. It presents the fully developed southern temple style as seen in the Arjuna Ratha. These form the basis of the temples to come in the later Chola, Vijayanagar and Nayaka periods. A portrait here of Narasimhavarman I is remarkable. Unlike the relaxed postures in the portraits of other Pallava kings, in the Adivaraha cave, this one is made just like a deity in a niche and is accorded strict frontal formality. The unfinished structure shows how the sculptors cut the stone from top to bottom, using the uncut rock below as a platform to work on.

The fifth temple of the group takes on an apsidal shape, which was not used very often in Indian temples. This is known as an elephant-back-shaped temple. Interestingly, the sculptors made an elephant adjacent to it, perhaps to illustrate the point.

GAJALAKSHMI, VARAHA CAVE, 7th century. Gajalakshmi has been a theme in Indic art since the Buddhist art of the 2nd century B.C.

GAJALAKSHMI, VARAHA CAVE, 7th century. Gajalakshmi has been a theme in Indic art since the Buddhist art of the 2nd century B.C.

One of the glories of Mamallapuram, built right next to the lapping waves of the sea, is a temple with two towers, known as the Shore Temple. The finely worked slender towers are among the most beautiful structures in the Indian subcontinent. The temple was probably made by Narasimhavarman II (Rajasimha) in the early 8th century. He is believed to have established the tradition of building structural stone temples in Tamil Nadu.

Below both the towers of the Shore Temple are shrines with Siva Lingas. The rear walls of both have relief panels showing Siva, Uma and their son Skanda. The group is known as Somaskanda, and it became the favourite icon in Pallava shrines. It also served as a metaphor for the Pallava royal family. A shrine in between the two dedicated to Siva has a depiction of the Anantasayana Vishnu. This was carved in situ out of an existing rock.

MAHISHASURAMARDINI CAVE, 7TH century. Even while great themes were made in rock-cut relief at Mamallapuram, caves were excavated out of the hills, continuing the tradition seen in western India.

MAHISHASURAMARDINI CAVE, 7TH century. Even while great themes were made in rock-cut relief at Mamallapuram, caves were excavated out of the hills, continuing the tradition seen in western India.

Over twelve hundred years of salt-laden winds have taken their toll on the temple, and the profusion of sculptures on it has been considerably eroded. However, what remains shows the highest standards of artistic achievement.

Perhaps, the most memorable aspect of the art of Mamallapuram is the depiction of the many beings that inhabit the world: deer, cows, elephants and others. Man is seen amidst the world of nature as one of its many manifestations. The Indian sculptor manages to communicate the living, breathing quality and emotions of animals with a rare empathy.

SOMASKANDA, SHORE TEMPLE. The favoured representation of Siva in the Pallava temples is of him with his wife, Uma, and son Kumara, or Kartikeya. The image may also symbolise the paternal benevolence of the Pallava ruler.

SOMASKANDA, SHORE TEMPLE. The favoured representation of Siva in the Pallava temples is of him with his wife, Uma, and son Kumara, or Kartikeya. The image may also symbolise the paternal benevolence of the Pallava ruler.

What gives the art of ancient India a special place is its vision of the world: a vision that sees the same in each of us, men and women, and in animals, plants, trees and even the breeze that moves the leaves. It sees a unity in the whole of creation, which imparts a great harmony and compassion to this vision. For a thousand years, the prolific creation of sculpture was an art sponsored by people.

Inscriptions and royal portraits show that by the 7th and 8th centuries, the Pallava kings began to take a direct interest in sponsoring art.

<< Back to home